Only fools and horses

Outside the criminal law fraternity, it’s not widely known that handling stolen goods attracts double the maximum prison sentence over plain theft:14 years to theft’s 7. Not so much counterintuitive as entirely logical because the fewer handlers there are the less theft: at least in theory. Drug dealing and personal possession could be couched in similar terms. So, what about online influencers promoting counterfeit goods? Well, the law hasn’t quite got its head around this rising modern phenomenon, so we’ll try and set out the issues for you.

Peddling fake goods was once the preserve of spivs in pork-pie hats standing on street corners, with enticing half open suitcases of ‘snide’ perfume, keeping a watchful eye out for the Rozzers. Now it’s online shopping platforms behind which exists mass, factory production of counterfeit goods. An industry with an estimated annual worth of $464 billion or, put another way, 2.5% of world trade.… and growing!

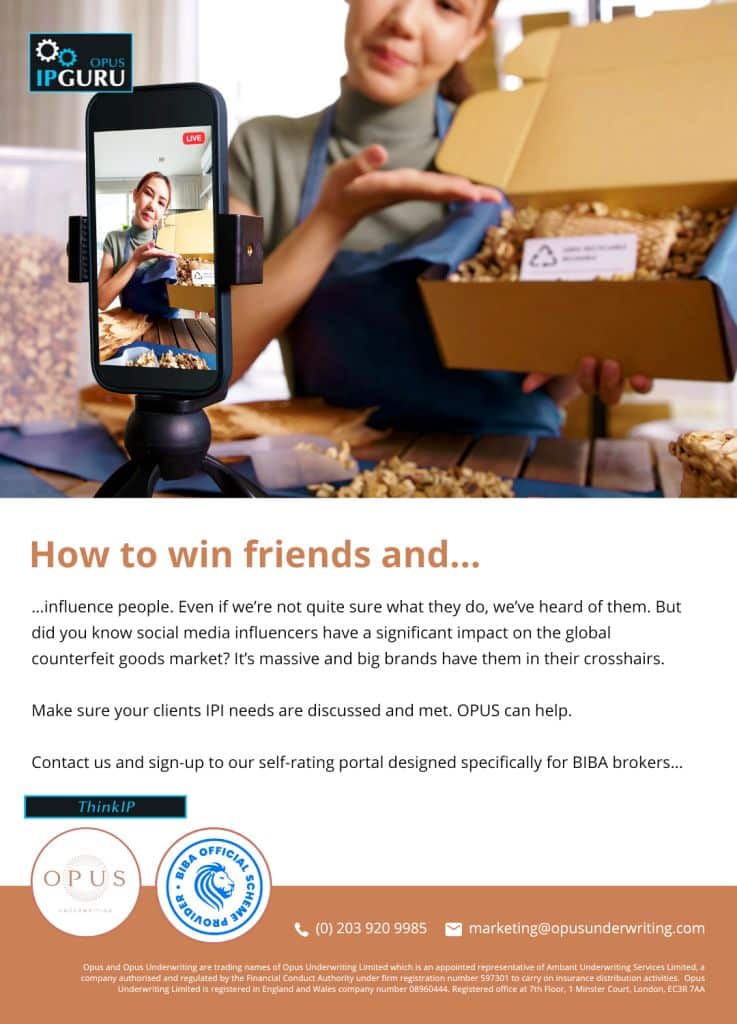

And in the middle of it all, we have the influencer slavishly followed by a cast of thousands for scraps of ‘useful’ information where never a surprise “CorBlimey Guv” is uttered.

How did we get here, who’s getting hurt and does any of this IP infringement really matter?

The perfect storm…

…behind which to flog counterfeit goods.

The rise of the internet has allowed influencers to generate content for millions of people around the world, giving them an unprecedented level of, well, influence. According to the online marketing specialist Social Shephard, the influencer advertising market reached a valuation of $21.1billion in 2023. As legitimate businesses increasingly take notice of influencers, so too does the counterfeit goods industry.

Influencers are a diverse crowd. Many know better than to sign-on to shady sponsorship deals, but not all. Despite creating media for thousands – sometimes millions – of fans, influencers usually work alone or in small teams. Seeking legal advice is an afterthought if it’s done at all.

What harm can it do to promote dodgy goods online?

Collars felt

For CEDAZ and Nicolas Tuinenburg – two famous influencers – their dealings landed them in court. Both sued by Nike after using their platforms to advertise counterfeit trainers.

Many of these goods come from companies such as PandaBuy. This notorious counterfeit business operates out of China and has blatantly used influencers to advertise its wares for years. It might seem strange that such illegal practises can happen so openly, but PandaBuy isn’t at risk here. The influencers and buyers take the risk.

Being outside the U.S. legal jurisdiction, Nike was unable to challenge PandaBuy directly. Instead, Nike focussed on stifling the source of demand for these counterfeit goods.

It remains to be seen if this will set the industry back long-term, or if new influencers emerge to replace those beaten back by the courts in a never-ending game of whack-a-mole.

Paved with gold

We can be certain influencers provide an unprecedented avenue to wealth for the counterfeit goods industry. Media once produced by experienced, regulated studios is now being created by a smattering of individuals across the world. Individuals tempted into becoming online traders of counterfeit goods that reach an army of dedicated fans, many being minors.

Should we care? Does ‘average Joe’ get hurt? Are influencers doing harm, or simply filling a gap in the market? Perhaps both.

Victimless crime?

Much depends on where you look for the evidence but consider the following possibilities:

- The poor and disadvantaged are often exploited in the production and distribution of counterfeit goods.

- Entire impoverished communities being ruthlessly exploited in some cases.

- Governments and society being deprived of legitimate tax revenue. (Quite what they might do with the additional revenue is a moot point!)

- Businesses losing revenue due to fake products.

- Shareholders/managed funds (possibly even pension funds) invested in such targeted businesses losing revenue if/when shares dive and devalue.

- The staff of these businesses being impacted with both jobs and pay coming under pressure.

- Counterfeit culture, in effect, supporting child labour, and the

- Boosting of organised crime.

- Health and safety of the purchaser being at risk should the fake product cause injury.

The list of probable victims goes on.

In February this year the UK Government published a research paper into:

“The impact of complicit social media influencers on counterfeit purchasing among male consumers in the UK”.

Granted, not the catchiest of titles but ‘bang on the money’ for this topic.

Key findings were deduced:

“Intellectual property rights underpin the innovation that drives the free-market economy and enhances the welfare of the public.”

Concluding:

“The illicit trade in counterfeit goods directly harms the market, hinders development and undermines public welfare”.

Grave and weighty stuff. Evidently, the research suggests quite a bit of damage is being done to society, businesses, and individuals. Often, it’s claimed, the young– especially teenagers- getting hurt most by this merry-go-round of searching for copies online, finding influencers on SM platforms typically leading to ‘hooky’ gear being promoted and delivered. And it gets worse…

The land of the wilfully blind

“Impact of social media influencers

- 31% of UK male participants aged 16 to 60 are influenced by SM endorsements in their purchases of counterfeits.

- 7% are counterfeit hunters who use the SM postings to assist in their searches.

- 24% are prompted by SM endorsements to buy counterfeits.

- 18% are knowing responders who are aware the products are counterfeit.

- 6% are deceived responders who are unaware the products are counterfeit.”

Surely, we just tell them it’s a jungle out there so watch out.

Buyer beware?

It looks like they already are…and not in a good way…

“35% of male consumers aged 16 to 60 knowingly buy counterfeits.

- 17% buy products that risk their health and safety.

- 60% of knowing buyers are aged 16 to 33 and generating 61% of demand.

- 36% of knowing buyers are habitual buyers, generating 67% of the demand.

Fashion, accessories, jewellery, and cosmetic products are the most popular product categories.”

We are witnessing, in plain sight, the roll out of a massive, modern problem. You rarely get heavyweight government-sponsored academic reports on inconsequential matters.

Forbidden fruit

Is today’s influencer a ‘fence’ or pusher? Or, just an easy target because most of us don’t think you should be able to make a living that way or that it should be ‘a thing’ at all. Because we don’t understand how influencer’s work – they must be to blame. Many would say that’s naff, intellectually lazy, ageist thinking.

Besides, that would fly in the face of the larger, statistically undeniable phenomenon of significant numbers of the public actively seeking cheap fakes. Is all this mess predicated on the simple fact greedy consumers just want a bargain and if an ex-contestant from a reality show or failed rapper can point the way – that’s fine. Forget the ragged, abject children involved in its manufacture, forget the threat of injury to body and pension fund, because your mates will be “well jell”.

A societally hideous notion but is it an alarmingly obvious conclusion. You decide. And more to the point, you and your wallet decide whether you want to be a part of it. Silence is rarely the answer and all too often the enabler. Heaven knows how you police this. You wouldn’t start from here…as the Irish answer to a request for directions goes. Locking up influencers is quite probably a futile gesture. Sometimes wars need futile gestures to pep up morale. We shall see. Friedman put it neatly:

“Is there some society you know that doesn’t run on greed?…None of us are greedy. It’s only the other fellow who’s greedy.”

Genies are not known to return unconditionally to their bottles and there’s always those three trouble some wishes…Canada Goose, Hermes, and Louis Vuitton?

Joseph Burton

Research Assistant

OPUS Underwriting Limited

+44 (0) 780 145 9940

underwriting@opusunderwriting.com