A yarn to spin

American hypocrisy?

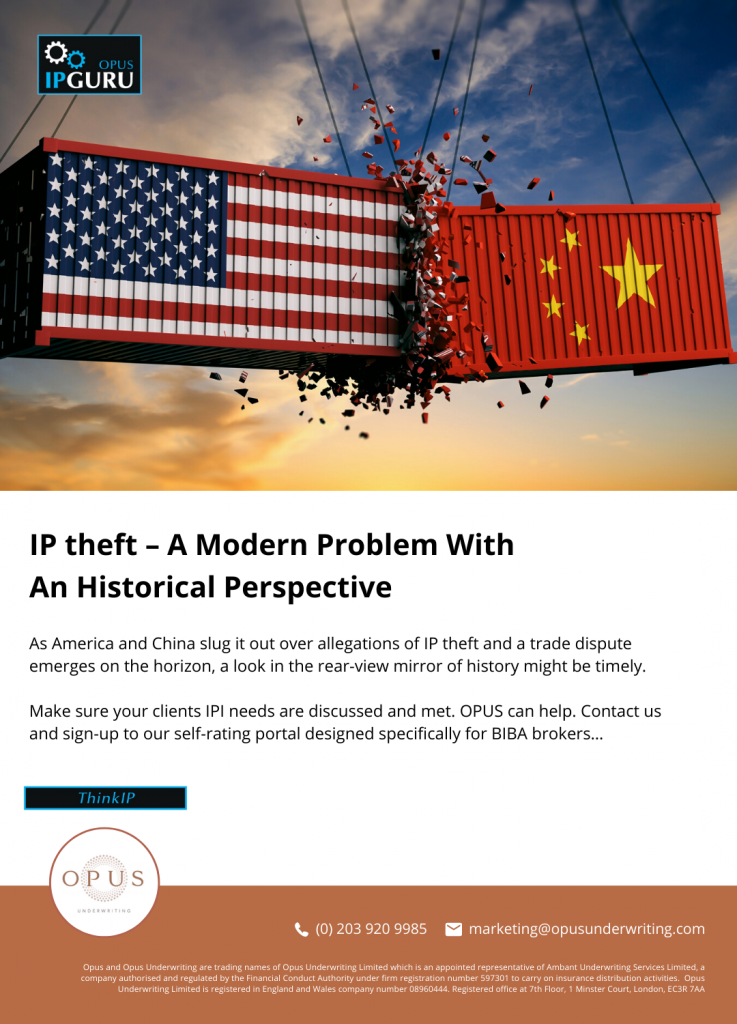

All too often we see the US call China an IP thief, accusing them of stealing American intellectual property. Under the so-called “Section 301 investigation”, Trump appeared to use the allegations of state-sponsored Chinese IP theft to trigger a trade dispute. Such allegations sow mistrust between both countries, engender disputes, rifts and general disharmony. Two questions emerge, is this new and is it fair?

The pilgrim’s tale

Samuel Slater aged 21, boards a ship in London bound for New York. He wants the good life. Nothing new in that. But the year is 1789 and Sam is travelling illegally not for trying to enter New York under the radar of the authorities, but because he’s not allowed to leave Britain. Why? Because he’s a recently qualified cotton mill apprentice having worked on Arkwright’s “water frame” technology. This made his skills as valuable as gold itself. In 1774, Britain sought to protect its mill industry (the Silicon Valley of its day) by criminalising the export of textile machinery and textile mechanics like Sam. Britain didn’t mind America producing bales of raw cotton because the real money to be made (fortunes in reality) was in the processing mills in Britain. America was struggling with its technology and Britain wanted to keep it that way. Remind you of any modern comparison?

Pilgrim’s progress

Back to the story, because you want to know what became of Sam. Within a year he created America’s first automated textile mill. It was a huge success. By 1815 there were 140 similar mills operating in excess of 100,000 spindles. America had caught up with Britain and its own industrial revolution had begun.

For Slater, he was lionised in the States and known as the “Father of American Manufacturers”. In Britain and Derbyshire, he was known as “Slater the Traitor”.

For some, this is all the evidence needed to show how the US kick-started their journey to manufacturing riches by stealing from Britain. It follows, they can’t now complain about China.

…a tangled web we weave…

It just isn’t that simple. Firstly, it is highly likely that Britain itself, throughout the 18thcentury, committed industrial espionage across Europe to gain commercial and production advantage. Let’s be open, Britain granted “patents of importation” precisely to encourage people to steal ideas from abroad and bring them home. Going back in time doesn’t help us.

Moving forward, these past IP thefts clearly led to current international treaties to guarantee foreign IP law, so we now have less of a free-for-all and a more cohesive, integrated environment for IP that assists and promotes contemporary global commerce.

So, is China off the hook? It does seem unfair to accuse China of IP theft when it was only a few decades ago that the US and China co-operated in technical advancements for mutual advantage. China might reasonably ask; when did such agreements end, and the allegations of theft begin? We didn’t get the memo’.

Moreover, the very nature of an under-developed country trying to catch up with a developed mentor is one of mimicry and reverse engineering. Inevitably, it takes time, as it did in Europe over the last 200 years, for IP laws to be developed and then observed.

Less table-thumping, more guidance and glance to the past might be a more balanced Executive Order.

Until then, protect all your IP where and when you can.

Murray Fairclough

Development Underwriter

OPUS Underwriting Limited

+44 (0) 203 920 9985

underwriting@opusunderwriting.com

Written and researched by Ben Fairclough