Home Spun

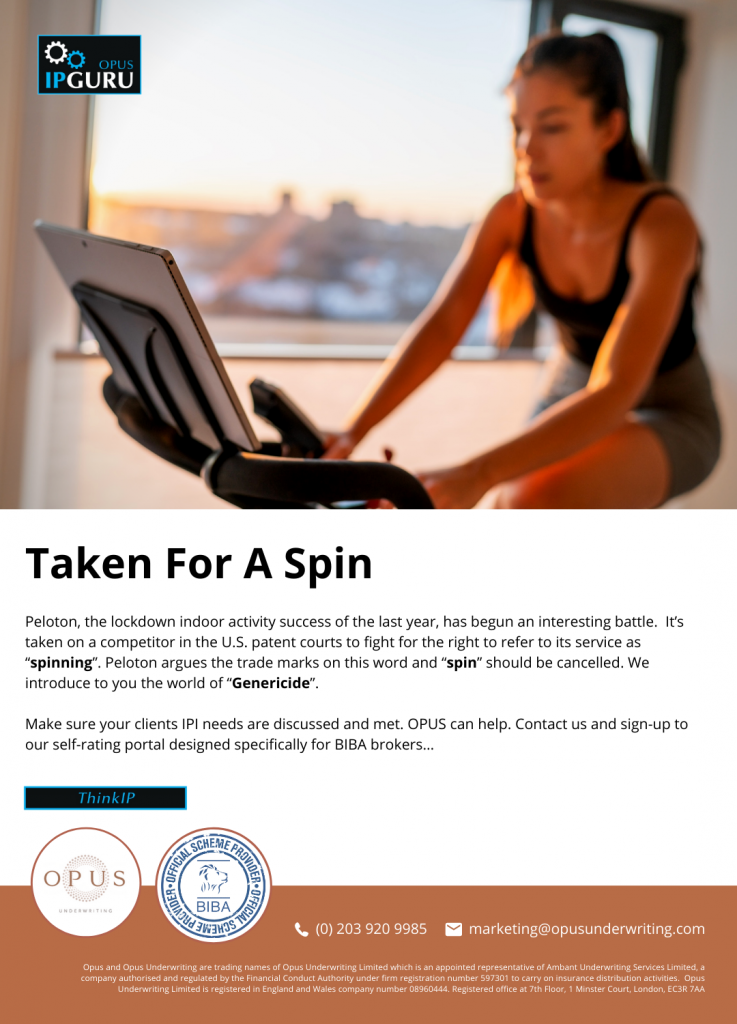

Work-out from home

Lockdown is a miserable state for most of us. For some, it presents opportunity. Wily stock-pickers will have looked closely at Peloton Interactive Inc. from April last year and taken a punt. They were wise to do so and will have enjoyed riding the wave of a 350% share price gain. Not difficult to spot in hindsight. A business based on interactive exercise from the comfort of your own home and out of the rain. What’s not to like. Only don’t refer to it as “on-line spinning” as that’s currently a matter of legal dispute.

Mad dogs bite

Peloton has filed petitions in U.S. courts looking to cancel a rival’s aging trade marks for the terms “spin” and “spinning” claiming they are now;

“…generic terms to describe a type of exercise bike and associated in-studio class”.

The rival, California-based Mad Dogg Athletics, says the terms are:

“…brand names that serve to identify the unique fitness products and programs offered by Mad Dogg Athletics, Inc,” and are important business assets to be treated with “care and respect”

Peloton alleges Mad Dogg is a corporate bully, threatening people and companies demanding they stop using terms they have every right to use. They go on to say in their filing with the Patent and Trademark Office’s Trademark Trial and Appeal Board:

“Spin class and spin bike are part of the fitness lexicon…”

There’s no unselfishness in Peloton’s action who, newly enriched, are forced to fight their corner and retaliate as Mad Dogg relentlessly pursues them for infringement. We must sit and wait to see who wins.

European straw in the wind

In 2014 there was a similar fight, this time on the battleground of Europe. Mad Dogg picked on a Czech company called Aerospinning Master Franchising Ltd. (AMF) and lost. AMF successfully filed for the trade marks to be cancelled on the basis they were no longer distinctive and had become generic.

So how do you prove a trade mark should be cancelled because, through common usage, it now fails to distinguish the origin of the goods and services from those of another? Well, there is a two-limb test in Europe and certain conditions must be met.

- It must be objectively established that the trade mark has become a generic term for the product or service for which it was registered; and

- The loss of distinctive character of the mark must have occurred because of the inactivity of the trade mark owner.

Cleverly, AMF undertook market research to establish that “spinning” had become a generic term for a type of sport activity, that is, an indoor cycling class and the mark did not indicate ownership by Mad Dogg. This was accepted by the court. Moreover, the court found Mad Dogg had not vigilantly protected the distinctive character of its trade mark “spinning”. And this despite over 700 legal actions in Germany alone with 50 of them successful!

Perhaps Mad Dogg was undone not by lack of effort in seeking to enforce its marks but by the fact they were common words. To the layman, policing the use of everyday words like “spin” and “spinning” does have the whiff of futility. And so, in Europe anyhow, we witnessed what is known in intellectual property circles as ‘Trade mark Genericide’.

Death of a trademark

To describe this phenomenon, think of the following words: “Thermos”, “Zipper”, “Fridge” and “Escalator”. All were once distinctive trade marks. Yes, really. And then they died due to their own excessive popularity by becoming descriptive (not distinctive) words for types of products.

How they die and become genericized is interesting. The trademark holder can often be to blame.

Firstly, it’s a fine line for mark holders wanting to make their trade marks popular and yet protect them from being synonymously used to describe a category of products. Spare a thought for Chrysler who invented “SUV” because they couldn’t use “Jeep” (it’s a registered mark) to face “SUV” itself becoming genericized.

And then there’s the subtle use of language that can undo ownership.

Using the mark as a verb not a proper noun, can be fatal. For example, “go and Google it”. Commonplace usage. Precisely the problem.

Another flaw is where the trade mark name is so much easier to say than to engage in an alternative description. Conveyor transport device or “escalator”? No contest, and the rot sets in.

Looking back, and with some irony, ‘first of a kind’ products are particularly prone to becoming genericized. With no competition and a rampant monopoly, they are often quick to become a synonym for that product or class of products. Popularity is a double-edged sword.

There are tips on how to avoid trade mark death. Here are a few:

- Avoid using the trade mark as a noun.

- Use the letter R enclosed in a circle for a registered mark or TM for an unregistered mark. This gives notice to users of ownership.

- Avoid plurals.

- Avoid using the mark as a verb.

- Try and use the trade mark on several products, not just one, think of a sportswear range.

- Object to any misuse and seek to educate on usage whenever an opportunity arises.

- Use capitals in the text to draw attention to the trade mark.

If Peloton and Mad Dogg slugging it out in the U.S. courts has put you off tonight’s on-line spin class, fret not, you could always burn the calories doing the hoovering.

Murray Fairclough

Development Underwriter

OPUS Underwriting Limited

+44 (0) 203 920 9985

underwriting@opusunderwriting.com

Written and researched by Ben Fairclough